An increase of platform work in the ‘gig economy’ signals a shift away from Australia’s standard employment model. The gig economy is a labour market comprising of independent contractors, online platform workers, contract firm workers, on-call workers and temporary workers. Most notable for its flexible nature, gig work offers individuals an alternative to a conventional 9-5 routine.

Gig economy work is increasingly common in the rideshare and food delivery industries and used by digital platforms to pair workers with various ‘tasks’ or ‘jobs’. It is likely you are already familiar with companies that adopt this new working model. For instance, Uber and Didi allow their drivers to “control whether, when, and for how long they will perform work on any given day”. [1]

Digital freelance platforms such as Upwork and Airtasker also make up a large portion of the gig economy. Upwork provides businesses with the opportunity to connect and collaborate with independent professionals across the globe.

Businesses can “hire a pro” across a number of different specialisations, including development and IT, admin and customer support and sales and marketing. These gig economy platforms are popular with companies who are looking to outsource particular tasks or projects. Outsourcing is a great way to cut costs, maximise productivity and tap into a global talent pool of experienced workers.

The Covid 19 pandemic has had a tremendous impact on the availability of jobs in the gig economy. Due to the ongoing disruption to Australia’s labour market, more people are turning to gig work to replace or supplement their existing income. The growing supply of gig economy workers is met by the surge in demand for contactless food delivery services. As social distancing and lockdown measures become the ‘new normal’, takeaway food deliveries are a popular option to reduce social interaction and curb the spread of the virus.

The distinction between employees and independent contractors

Australia’s workplace laws traditionally distinguish between two types of workers – employees and independent contractors.

An employee is typically engaged by another person or business. Under the Fair Work Act, many benefits and entitlements are reserved exclusively for employees.

In contrast, an independent contractor is normally self-employed and can sell their services and labour to more than one business. These workers retain the discretion to decide how and when to do the work.

In the absence of a conclusive, statutory definition, the question of a worker’s status for the purposes of the Fair Work Act is determined by a set of established common law principles. In Hollis v Vabu, the High Court of Australia set out a ‘multi-factor’ test of employment to classify workers as either independent contractors or employees.

Upon application of this test, a court must examine the “totality of the relationship” between an individual and their employer. This assessment requires consideration of both contractual terms and actual work practices. The outcome will ultimately depend on the facts in any given case.

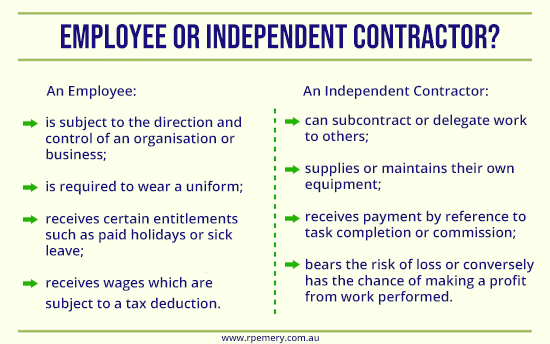

Australian courts generally regard the following factors as strong indicators of employment status. The worker:

- is subject to the direction and control of an organisation or business;

- is required to wear a uniform;

- receives certain entitlements such as paid holidays or sick leave;

- receives wages which are subject to a tax deduction;

The following factors alternatively support a finding that a worker is an independent contractor. The worker:

- can subcontract or delegate work to others;

- supplies or maintains their own equipment;

- receives payment by reference to task completion or commission;

- bears the risk of loss or conversely has the chance of making a profit from work performed.

The working arrangements between rideshare drivers and digital platforms such as Uber do not fit neatly within either of these distinct categories. Uber has long maintained its drivers are independent providers of delivery services. However, the company has faced numerous legal challenges across the globe for classifying its workers as such.

Gupta v Uber

In the leading case of Gupta v Uber, the Fair Work Commission concluded that Uber drivers are independent contractors and not employees under Australian law.

Amita Gupta performed delivery services for Uber Eats across a period of 18 months. After allegedly failing to provide customers with their food on time, Uber permanently blocked Ms Gupta’s access to the delivery partner app. In response, Ms Gupta lodged an unfair dismissal claim with the Fair Work Commission.

The Commission ultimately ruled that Ms Gupta could not claim unfair dismissal because she was an independent worker rather than an employee. One of the most significant factors informing the decision included Uber’s lack of control over how Ms Gupta performed her work. Specifically, Ms Gupta retained the right to choose when she logged on to the Partner app and accept an assignment. The Commission also noted that Ms Gupta could accept work from other delivery platforms and was not required to wear a uniform.

In her defence, Ms Gupta emphasised the fact that Uber required food delivery riders to adhere to strict guidelines and an automated rating system. However, the Commission concluded that there was “nothing particularly unusual about a principal establishing and enforcing performance and quality standards in respect of independent contractors engaged to perform work” [2]. This finding demonstrates the unpredictable nature of the ‘multi-factor’ approach and how certain facts can be attributed particular weight over others.

The consequences of this classification are far-reaching in respect to the basic rights that gig economy workers such as Ms Gupta would otherwise be entitled to under the Fair Work Act. The case ultimately confirms that digital platforms are not obliged to provide their drivers with minimum wage entitlements, sick leave, holiday pay or annual leave benefits. Whether or not an Australian court will uphold the Commission’s decision remains to be seen.

Why is this classification important? The dangers of ‘sham contracting’

As the gig economy gains increasing momentum, regulatory bodies and Australian courts are paying close attention to ‘sham contracting’ practices.

A ‘sham contract’ arises when an arrangement is really an employment relationship but has been constructed as an independent contractor arrangement to avoid employment obligations. To illustrate by way of a famous analogy, parties cannot merely create “something which has every feature of a rooster, but then insist on calling it a duck” [3].

Deliberately disguising an employee as an independent contractor in this way can attract hefty penalties under the Fair Work Act. The maximum penalty currently stands at $13,320 for individuals and $66,600 for corporations.

Online food delivery platform Foodora has recently landed itself in hot water for underpayment of wages. In 2018, the Fair Work Ombudsman commenced legal proceedings against the delivery giant, alleging that it had misclassified its employees as independent contractors. Following an investigation into the issue, the Ombudsman found that Foodora underpaid three delivery workers a total of $1,620 plus superannuation across a period of four weeks [4].

Unfortunately for these food delivery workers, Foodora publicly announced its decision to exit the Australian market before the Federal Court could make its ruling. The company has since entered into voluntary administration.

Nonetheless, the proceedings illustrate that the exploitation of workers’ rights by way of sham contracting will not end well for businesses in the long run.

Important Tools and Resources for Employers

As a business, you should undertake regular reviews of any existing or prospective arrangements you have with your workforce. There are several valuable sources available online to assist you. However, if still in doubt, you must seek legal advice as soon as possible.

The Fair Work website has tools and guidelines dedicated to assisting businesses to determine whether someone is an employee or contractor.

The Australian Taxation Office has resources and tools available to assist businesses in deciding whether they are hiring an employee or contractor.

To minimise any potential for misunderstandings and conflict, we also recommend having a written contract in place to state the precise nature of a worker’s status.

Here at RP Emery, we offer a range of professionally drafted employment and contractor contracts that contain all the necessary terms and conditions required to comply with Australian labour law.

Our agreement templates are formatted in Microsoft Word for easy editing and come with a comprehensive set of instructions. Simply download your document, edit and print.

Visit this link for more information about employment resources in Australia or contact us today to discuss which agreement will work best for you and your business.

By Kirra Griffin May 2021

Kirra Griffin is a final-year law student at Melbourne Law School. As our resident legal assistant, Kirra uses her specialised knowledge of the law to translate complex concepts into easily digestible information.

Kirra Griffin is a final-year law student at Melbourne Law School. As our resident legal assistant, Kirra uses her specialised knowledge of the law to translate complex concepts into easily digestible information.

Other Articles and Resources

What types of employees do you have? Are you meeting your obligations?

Thanks to an increasingly flexible workplace, it seems like when it comes to employee contracts, almost anything goes. But It’s important to classify your employees correctly so that they receive all their entitlements under the law and you comply with the legislation.

Thanks to an increasingly flexible workplace, it seems like when it comes to employee contracts, almost anything goes. But It’s important to classify your employees correctly so that they receive all their entitlements under the law and you comply with the legislation.

Streamline the process of employing new staff by using Employment Contract Templates

Employment Contracts are ideal discussion points to be referred to when interviewing, recruiting and hiring staff. As the contracts cover the essentials, by working your way through the contract you can make sure you are not missing anything important.

Employment Contracts are ideal discussion points to be referred to when interviewing, recruiting and hiring staff. As the contracts cover the essentials, by working your way through the contract you can make sure you are not missing anything important.